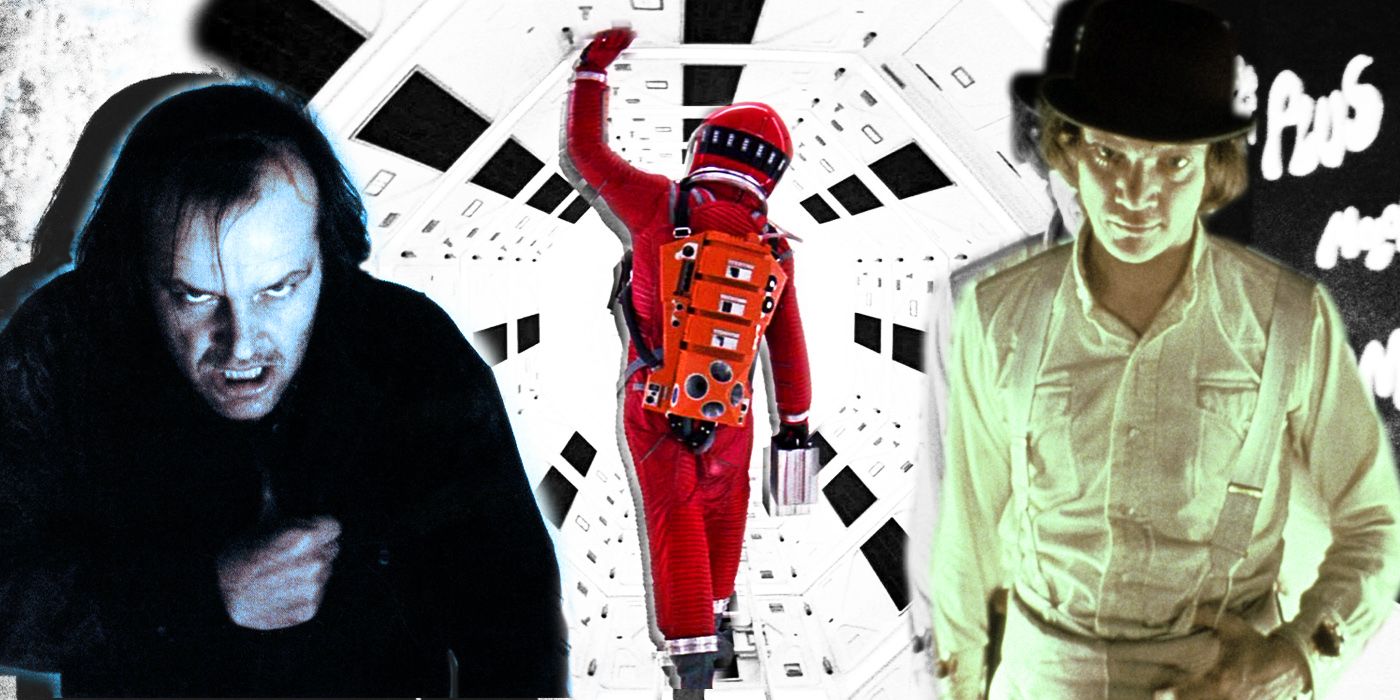

Stanley Kubrick directed 13 feature-length movies during his impressive career, and it can be difficult to rank them from worst to best. Born in the summer of 1928, Stanley Kubrick is regularly and deservedly regarded as one of the best filmmakers and directors in the history of cinema. Kubrick's films occupy their own corner of the cinematic matrix: other movies revolve near and around Kubrick's films, but few reach their artistic grandeur. Kubrick's films were visually and thematically groundbreaking, and many of today's filmmakers draw inspiration from his movies.

Stanley Kubrick was infamously meticulous. Obsessed with the aesthetics of his productions, calling Kubrick a perfectionist would be an understatement (just ask Shelly Duvall). But in any case, no matter what torture he put his co-workers through, be it his performers, his producers, his camera crew, his makeup crew, or his catering crew, the fact remains that Kubrick created some of Hollywood's best movies. In an era of filmmaking where the common aesthetic approach is that of a singular, overarching tone — see the ferocious debate surrounding The Rise of Skywalker's artistic merit — watching a director with a consistently distinct vision is something worth appreciating.

In fact, watching Kubrick's films is such an enjoyable experience that ranking them is a tedious, thankless task. With many of them considered to be authentic masterpieces, there comes a point in the legendary director's filmography where comparing his films seems redundant. Regardless, here are all 13 of Stanley Kubrick's movies, ranked from worst to best.

Every filmmaker has to start somewhere, and Stanley Kubrick got his on the 1953 war drama Fear and Desire. Centered around four soldiers in an unspecified conflict (Frank Silvera, Paul Mazursky, Kenneth Harp and Steve Coit), the film follows the group as they attempt to survive behind enemy lines. Kubrick sought to keep this film out of circulation, embarrassed by its comparatively dodgy filmmaking. But even so, curious Kubrick fanatics should seek the film out, if only to see where the director first set his footing.

Like Fear and Desire, Kubrick's sophomore film, 1955's Killer's Kiss, was financed almost entirely by the director's friends and family. Starring Frank Silvera again, this time alongside Irene Kane and Jamie Smith, the film follows a washed-up boxer (Smith) as he attempts to rescue a beautiful dancer (Kane) from her aggressive and violent boss (Silvera). Though the movie is a noticeable step up from Fear and Desire, especially in terms of its visual aesthetics (a gloomy black-and-white production for which Kubrick also acted as its cinematographer), it is clear that the film-noir still has its fair share of kinks.

Widely considered to be Kubrick's most divisive and controversial, Eyes Wide Shut had the terrible misfortune of being the filmmaker's last. This isn't a criticism of the film in the slightest (though being his last may have brought the film an unjustified amount of pressure), it's just a nod to the fact that the director died only six days after showing his final cut to Warner Brothers. But even so, with its more hipster style — banked heavily on the excessively eccentric lead performance by Tom Cruise — combined with its director's trademark visual approach, the bizarre and sexually-charged film made for a suiting, if disappointing, swan song.

The 1960 film Spartacus is perhaps the most "Hollywood" film Stanley Kubrick ever made. Personally produced by its star Kirk Douglas from a script by then-blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, the film was a commercial and critical success at the time of its release. Although it won 4 Academy Awards, including one for supporting actor Peter Ustinov, as well as cinematography and costume design, the film has a considerable pacing problem. Not even the tense gladiator sequences and sharp political undertones can justify its taxing 200-minute runtime. Furthermore, the film lacks the director's trademark visual aesthetic and controversial themes. On the other hand, many aspects of Spartacus still hold up, and is certainly a better film than a #10 ranking would suggest.

Lolita is the film that makes Eyes Wides Shut's label of the most controversial of Kubrick's career debatable. Telling the story of a middle-aged professor (James Mason) falling in love with a 14-year-old "nymphet" (Sue Lyon), Kubrick had the remarkably difficult task of channeling the drama from Vladimir Nabokov's novel, while also keeping the sexuality tight — all while appeasing the then-strict censors. The director later said that he would have never done the film if he'd realized the losing battle he would've trudged against censors. But, given the surprising humor elicited in Lolita, as well as the fantastic performances from Mason and Peter Sellers (more on him later), losing this movie would have been a terrible shame.

When it came to his early work, the third time was the charm for Kubrick. Following a troupe of thieves as they attempt to pull off a race-track robbery — the last of career crook Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden) — The Killing is a tough noir, a gritty heist movie that exercises purely in the artistic style Kubrick would later master.

For Kubrick fans, the ranking of Full Metal Jacket has been a splitting issue. Surely, the most prominent reason for that is that the film itself is split, with the first half being a wickedly scary and humorous procession, and the latter half being, for lack of a better phrase, just alright. There are things to enjoy after Joker (Matthew Modine) and Cowboy (Arliss Howard) graduate from Sgt. Hartman's (R. Lee Ermey) brutal boot camp and hop over to Vietnam, but even in battle, the events never get as tense, explosive, or loud as when Ermey shouts at the poor Pvt. Pyle (Vincent D'Onofrio).

The prolific satire at the forefront of A Clockwork Orange has become such an ingrained and cherished piece of popular culture that it's easy for one to forget how challenging the film was to get made. The only X-rated production Kubrick ever put together (Kubrick later cut parts of the film to give it an R-rating), and adapted from Anthony Burgess' quirky, dialect-driven book, it tells the story of a group of "ultraviolent" delinquents in a dystopian future. The film is alarmingly cinematic, with the camera, the settings, the costume design, and the acting making the repulsive decisions and acts on the screen sneakily entertaining. The viewer isn't supposed to find rape, murder, robbery, and police brutality amusing, but being slyly seduced by the experience of A Clockwork Orange is the whole point.

The Shining is Stanley Kubrick's most atmospheric film. Adapted from the Stephen King novel of the same name, the movie follows the Overlook Hotel's off-season overseer Jack Torrence (a brilliantly eerie Jack Nicholson) and his family as they try to muster through a brutal winter. Soon, ghoulish trepidations start to take over Jack, and the hotel's walls come springing to life. With perhaps the most encompassing, alarming and underrated soundtrack in horror film history, The Shining is the kind of movie that isn't terrifying at face value: it's one in which unease gradually develops over time, boiling and boiling until it finally bubbles over in a suspenseful and gruesome finale. While it may be hard to manage, this is one Kubrick film that's best seen on the big screen.

Barry Lyndon is one of the most methodically beautiful films ever made. Following the titular character as he wiggles his way up to the top of the aristocracy of 18th-century England, there isn't a single moment in the movie that doesn't feel packed with emotion. The film is also impossibly beautiful, and perfectly captured; made only 20 years after his first cinematography gig, one can only hope that they can become a master of their craft in such a comparably short amount of time and practice (only 8 films after Killer's Kiss).

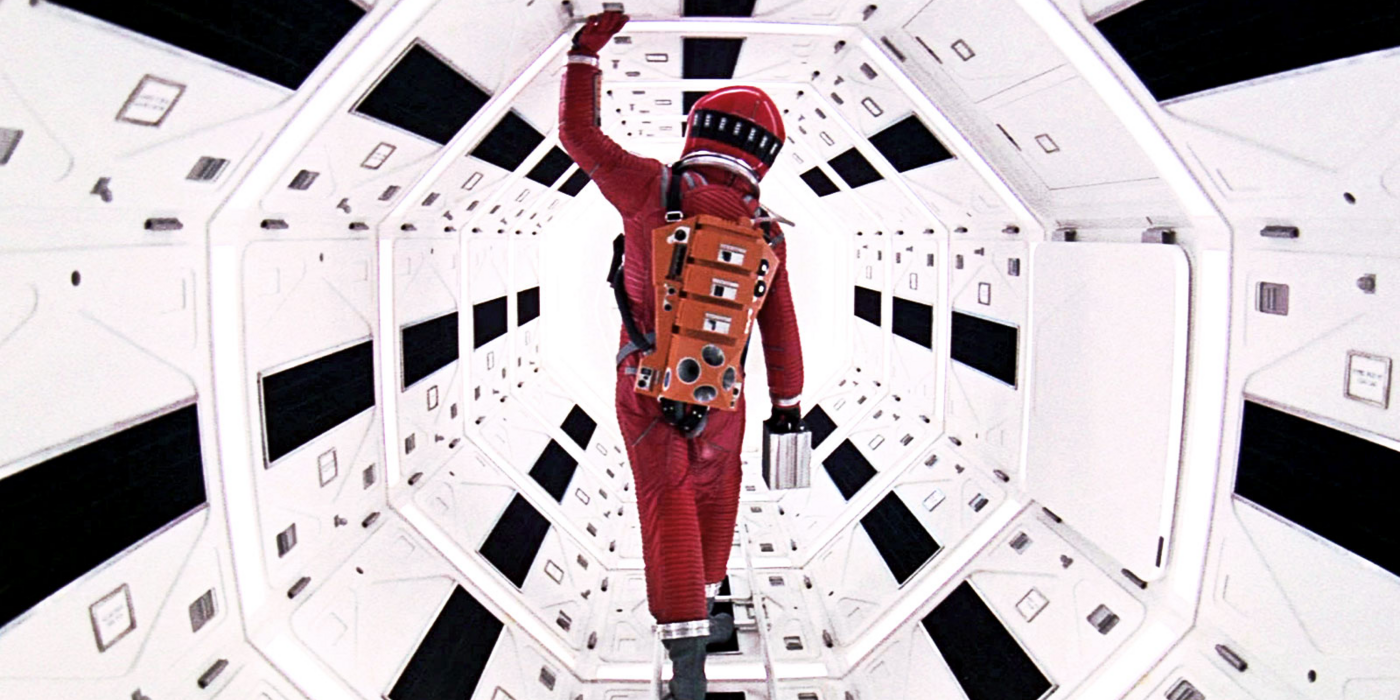

Regularly considered to be one of the greatest films ever made, perhaps a more fitting description for 2001: A Space Odyssey would be the most cinematic film ever made. Formulated before the Science-Fiction genre was redefined by the arrival of Star Wars, 2001 crafted a blending narrative between space, humanity, and Earth that may have even transcended the director himself. The film itself is showered with images and scenes that have since inspired a generation of filmmakers — be it the deadly red stare of HAL, the bone-beating monkey, or the movie's final extra-terrestrial creature — and shows how remarkable of an artist, visionary, and thinker Kubrick was. That being said, in capturing the essence of space, the film also captures the pacing of space: motionless. Though that's a slight exaggeration, 2001 is surely not the most watchable of his films, even if it is the most thematically stimulating.

There's a quote that is often attributed to late French filmmaker François Truffaut: "there's no such thing as an anti-war film." The notion suggests that because of the visual splendor that goes into making a film enticing and entertaining, there is no way to make a war film that accurately depicts the experience of war. Paths of Glory, Kubrick's viciously underrated World War I feature, debunks that theory. Set deep in the French trenches of World War 1, it stars Kirk Douglas as a colonel who must defend his soldiers in court after they are falsely vilified for refusing to jump into certain death. Unlike some of his more profound or ambiguous films, Paths of Glory's power can be found in its simplicity: no one should ever have to trudge through the experience of war.

Speaking of anti-war films, Dr. Strangelove finds Stanley Kubrick at his most cynical on the topic. Under the guise of a dark, satirical comedy, the director points fingers every which way at the total absurdity of nuclear warfare — and uses sharp satire to flaunt his disgust. Interweaving the narratives of a red-hot general who's given the go-ahead for nuclear annihilation with that of the incompetent world leaders who're tasked with cleaning the mess, Dr. Strangelove's reserved sense of comedy is its greatest weapon. Spearheaded by three lead performances from Peter Sellers, the cast also includes ridiculously over-the-top turns from George C. Scott, Slim Pickens (who engages in one of the most horrifically iconic shots in film history), and Sterling Hayden, the movie acts as a mirror for a society on the brink of totally and fully destroying itself. In being so, it is one of, if not the, greatest political satire in film history.

from ScreenRant - Feed https://ift.tt/2Ralhch

via IFTTT

0 comments:

Post a Comment