For over 40 years since the debut of the original Star Wars, the franchise's depiction of its villains has shifted and evolved with each trilogy. Audiences were captivated by the struggles of the Rebel Alliance, with the story of Luke Skywalker and his closest allies at the heart of it all. At the same time, the looming shadow of the Galactic Empire was just as interesting, with shadowy villains such as the sympathetic Darth Vader and the authoritarian Emperor rising to challenge the heroes at every turn.

16 years after the epic conclusion to George Lucas' Original Trilogy, the director returned to the Star Wars universe with The Phantom Menace, the first of his divisive prequel trilogy. Gone were the insurgent struggles against a sprawling governmental force, replaced by a politically-driven battle between the Galactic Republic's clone army and the Confederacy of Independent Systems' droid soldiers. Behind both factions were a far-reaching political conspiracy, unraveled just as the fate of the galaxy began to turn towards an unavoidable conclusion. Then, in 2015, audiences found themselves once again thrust into the middle of a hopeless conflict with Star Wars: The Force Awakens, as a new Resistance fought desperately against the crushing military might of the First Order.

The main Skywalker saga has become a massive nine-film epic at this point, each chapter filled with a new conflict and new villains. And while those villains may share some similarities among themselves, every trilogy brings a host of differences and new perspectives; some black and white, some nuanced, and some a bit more confusing than others.

Lucas' Original Trilogy, which follows the underdog Rebel Alliance as they fight to free the galaxy from the iron grip of the Galactic Empire, doesn't shy away from its real-world influences. The authoritarian rhetoric and style of governance employed by the Empire is a direct mirror of the fascist ideologies promoted by Adolf Hitler at the height of Nazi Germany's power. There are also aesthetic influences borrowed from the Nazis, such as the uniforms of the Imperial Officers being made to resemble those worn by the German Army in World War 2. The most obvious parallel is in the shared name used to reference both Galactic Empire grunts as well as the paramilitary foot-soldiers of the Nazi Party: Stormtroopers.

These similarities were used to contrast the traditional good versus evil conflict at the heart of Star Wars. Lucas was heavily influenced by the studies of Joseph Campbell regarding the Hero's Journey archetype, as well as a host of other mythological and theological sources. The result is a larger than life clash in space that feels like a battle between ancient mythic forces, something that contributes to the overall "legendary" feeling that Star Wars has.

The Prequel Trilogy, which sought to explain the origins of the Galactic Empire and Anakin Skywalker's fall from grace, operated in an area of relative nuance compared to the conflict of the OT. Lucas gave audiences a vision of a Jedi Order that had become docile and self-righteous, a far cry from the defenders of peace and justice that Ben Kenobi (Alec Guinness) had mentioned in A New Hope. On top of this, Attack of the Clones introduced the infamous Clone Army, an entire infantry force genetically replicated from the DNA of Jango Fett (Temuera Morrison). Attack of the Clones doesn't dive into the moral implications of such an army, but Star Wars: The Clone Wars does a fantastic job of humanizing each individual clone and exploring their personalities and distinct relationships with each other. Of course, this sets up the inevitable "Order 66" twist to be even more heartbreaking, because audiences now understand that the clones were always bred for this, despite their personal attachments.

There's also a hidden Nazi parallel underneath all of this political intrigue. Lucas titled the first of the prequel films The Phantom Menace because of the presence of Darth Sidious, posing behind the scenes as the unassuming Senator Palpatine. His rise through the political circuit (first as a champion of democracy, then inevitably as the Emperor of a Galactic Empire) eerily resembles Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 30s. This adds a sinister undercurrent to the Clone Army's genetic predisposition - similar to the claims of Nazi SS troopers, the Clone Troopers were also "just following orders." The decision to implant those orders into the brain of each clone literalizes that justification in an eerie way, and deepens Star Wars' overarching parallel to Nazi Germany.

Back in 2012, Walt Disney purchased Lucasfilm and Star Wars from George Lucas for over $4 billion, and quickly set about reintroducing the property into pop culture. This finally landed in theaters with 2015's Star Wars: The Force Awakens, which introduced audiences to a new story while still playing around with some of the universal visual and contextual language which had become associated with Star Wars. This includes the overt Nazi parallels; although this time they weren't coming from the Empire, but the First Order, an authoritarian military regime that worshipped the ideology of the Galactic Empire and figures like Darth Vader and the Emperor. Director J.J. Abrams himself has commented on the similarities, citing Nazis moving to Argentina and regrouping in the aftermath of World War 2 as a big influence on the history behind the First Order.

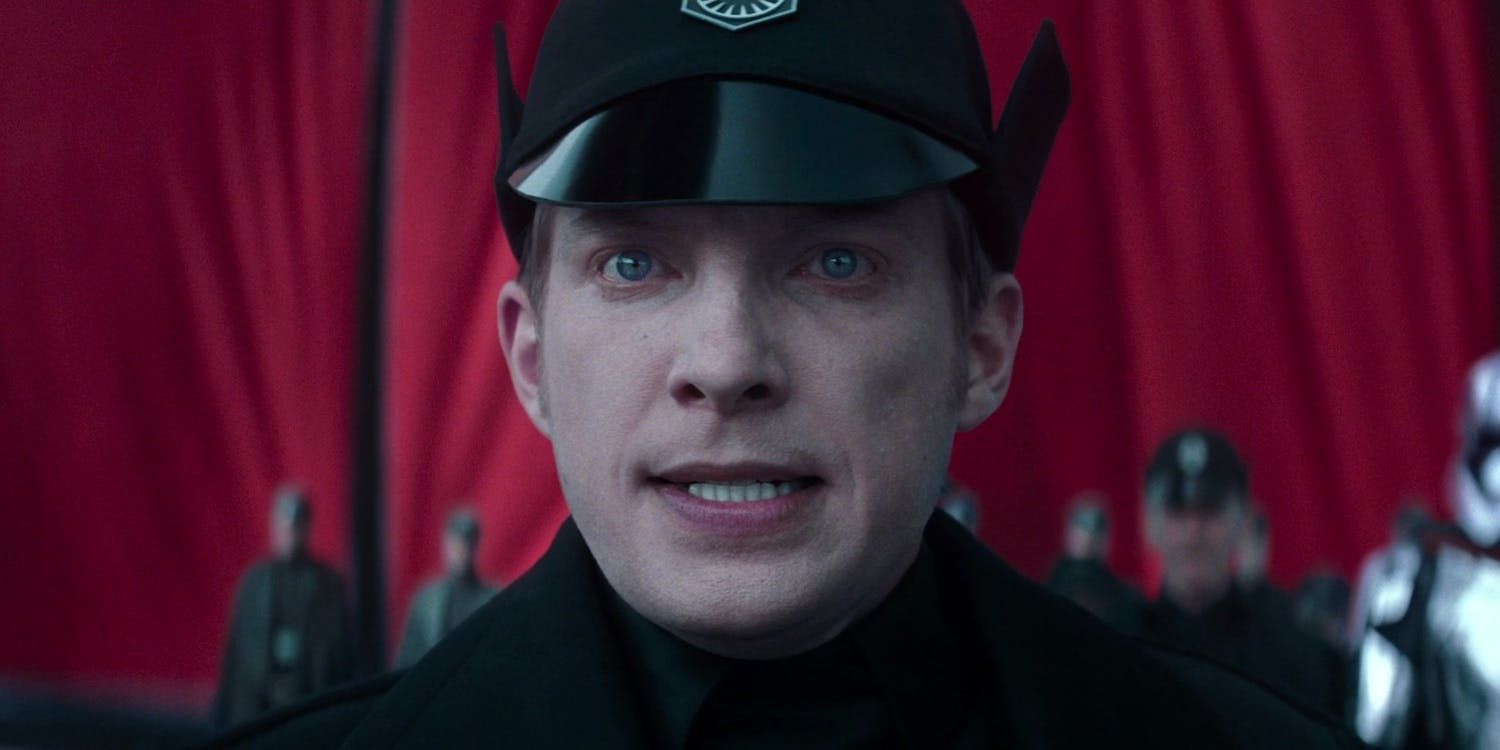

The result is aesthetic parallels such as General Hux's speech in The Force Awakens, which feels like an address that could be delivered right from the mouth of Adolf Hitler himself. Even Kylo Ren, the Sith-adjacent enforcer of the First Order, worships at a literal altar to Darth Vader, a figure complicit in atrocities of a galactic scale. Where this distinction gets confusing in the Sequel Trilogy is the way that Disney has marketed the films, and particularly the First Order.

Despite the obvious thematic Nazi references, Disney continually markets the First Order in a way that tries to appeal to their "cool" factor - their visual aesthetic, the Stormtrooper designs, and Kylo Ren's (Adam Driver) mystique. There's evidence of this everywhere, from roving bands of First Order troops patrolling Disney World, to toys and tie-in marketing pushing kids to side with the First Order in binary "pick a side" campaigns. While it isn't necessarily done maliciously or with a sinister mindset, there is a troubling confusion of intent behind the distinct visual language being used and the attempt to market these things in a way that children can digest.

This conflicting dichotomy also affects the stories that these villains receive in the Sequel Trilogy. There's an emphasis on humanizing the villains to the point of sympathy, and while this isn't expressly wrong, it does muddy the waters of Star Wars' mythic "good vs evil" conflict. While the lines are clear in the Original Trilogy (the Rebel Alliance are the good guys and the Empire are the bad guys), the Sequel Trilogy purposely blurs that division with characters such as Kylo Ren, the conflicted son of Han and Leia, who was turned on a dark path after his perceived betrayal at the hands of Luke Skywalker. Even General Hux gets a late-game attempt at partial redemption in The Rise of Skywalker. While this attempt at moral nuance isn't inherently bad, it clashes with the simplistic binary conflict that has driven the franchise in the past. While modern audiences expect more nuance in morality of their villains, Star Wars is to grow in its storytelling, it must choose which path it wants to follow in terms of their villains.

from ScreenRant - Feed https://ift.tt/36BwGHX

via IFTTT

0 comments:

Post a Comment