Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings trilogy proved to be a cinematic masterpiece - but many filmmakers had tried, and failed, to make the films before. J.R.R. Tolkien was one of the greatest fantasy writers of all time, and with the benefit of hindsight it was inevitable his books would become blockbusters. And yet, it took surprisingly long for Tolkien's works to triumph on the big screen.

The initial problem was Tolkien himself. Tolkien was exceptionally detail-oriented even by the standard of fantasy writers, and he doesn't appear to have been particularly appreciative of attempts to adapt his work. As he wrote in response to one script, "I would ask [the scriptwriters] to make an effort of imagination sufficient to understand the irritation (and on occasion the resentment) of an author, who finds, increasingly as he proceeds, his work treated as it would seem carelessly in general, in places recklessly, and with no evident signs of any appreciation of what it is all about." While Tolkien understood film is a different medium, he did not believe the conventions should differ too greatly, and hence resisted significant alterations. After his passing, studios wrestled with the fear his fans would share the same view.

Some animated and even TV adaptations did manage to get off the ground, but they received a mixed reception. Consequently, when Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring released in 2002, many viewers felt as though it was the first real blockbuster version of the iconic story. And they were frankly glad they had waited because while Jackson did make changes, his love for the original books was evident throughout. What's more, it was clearly evident the stories would not have been possible had VFX technology not become sufficiently advanced - and even then, the creative team had to make major innovations, most famously with Gollum. Still, for all these earlier adaptations would have failed to achieve the acclaim of Jackson's movies, they offer a fascinating glimpse into the franchise as it might have been. Here's your guide to all the unmade Lord of the Rings movies.

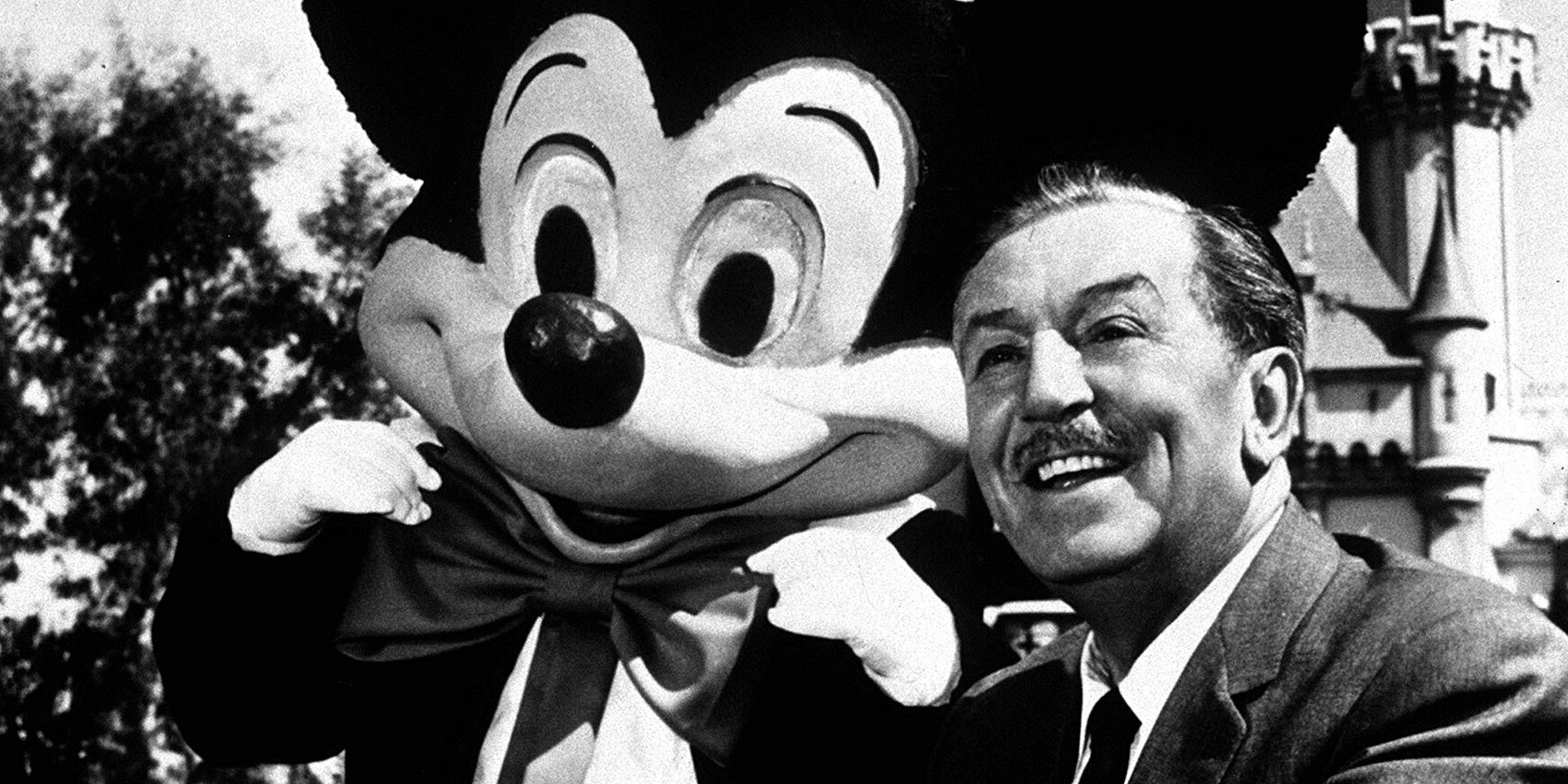

In a curious coincidence of timing, The Hobbit released just months before Disney's Snow White - and neither Tolkien nor his friend C.S. Lewis were impressed. Tolkien's dislike appears to have only increased over the years, and in a 1964 letter he described Walt Disney as "simply a cheat" who was "hopelessly corrupted" by profit-making. While Tolkien's publisher did approach Disney with the idea of an adaptation, it's generally believed they did so without Tolkien's consent, and they were initially turned down. Walt Disney did briefly reconsider in the 1950s, but according to animator Wolfgang Reitherman his storyboard artists believed The Lord of the Rings was too complex, lengthy, and scary for a Disney production.

Animator Al Brodax reached out to Tolkien and his publishers to propose an animated adaptation in the 1950s, but nothing came of it. Shortly after, Tolkien began to coordinate with Forrest J. Ackerman and screenwriter Grady Zimmerman, and at first things looked hopeful. Tolkien was impressed by concept art from illustrator Ron Cobb, who scouted locations around California. Unfortunately the script proved a problem, with Tolkien penning a lengthy and frankly scathing response. Zimmerman's script is part of the Marquette University Tolkien Collection in Wisconsin, and it took phenomenal liberties with the books. Several character arcs were reduced, female characters, in particular, were cut to a minimum, and entire action sequences were added. Strangest of all, a very different ending saw Sam steal the One Ring from Frodo and take it to Mount Doom himself, only to be attacked at the final moment by both Sam and Gollum. Ackerman was ultimately unable to secure a producer, and the project floundered. Zimmerman, for his part, abandoned his dreams of writing a movie altogether.

In 1959, author Robert Gutwillig contacted Tolkien with the idea of creating a Lord of the Rings movie. Tolkien was initially receptive, noting he had "given a considerable amount of time and thought [to this], and have already some ideas concerning what I think would be desirable, and also some notion of the difficulties involved, especially in the inevitable compression." First talks were positive, with Tolkien impressed by Gutwillig's agent Sam W. Gelfman, but sadly nothing ever came of the idea.

Moving into the 1960s, Rembrandt Films successfully negotiated the rights to The Hobbit, and there are conflicting accounts as to whether or not they also acquired the rights to The Lord of the Rings. The company ultimately created an animated short of The Hobbit in order to prolong his ownership of the rights, and it was only ever shown once in a projection room at New York to a group pulled from the street. Somewhat unsurprisingly, they never got anywhere with making The Lord of the Rings.

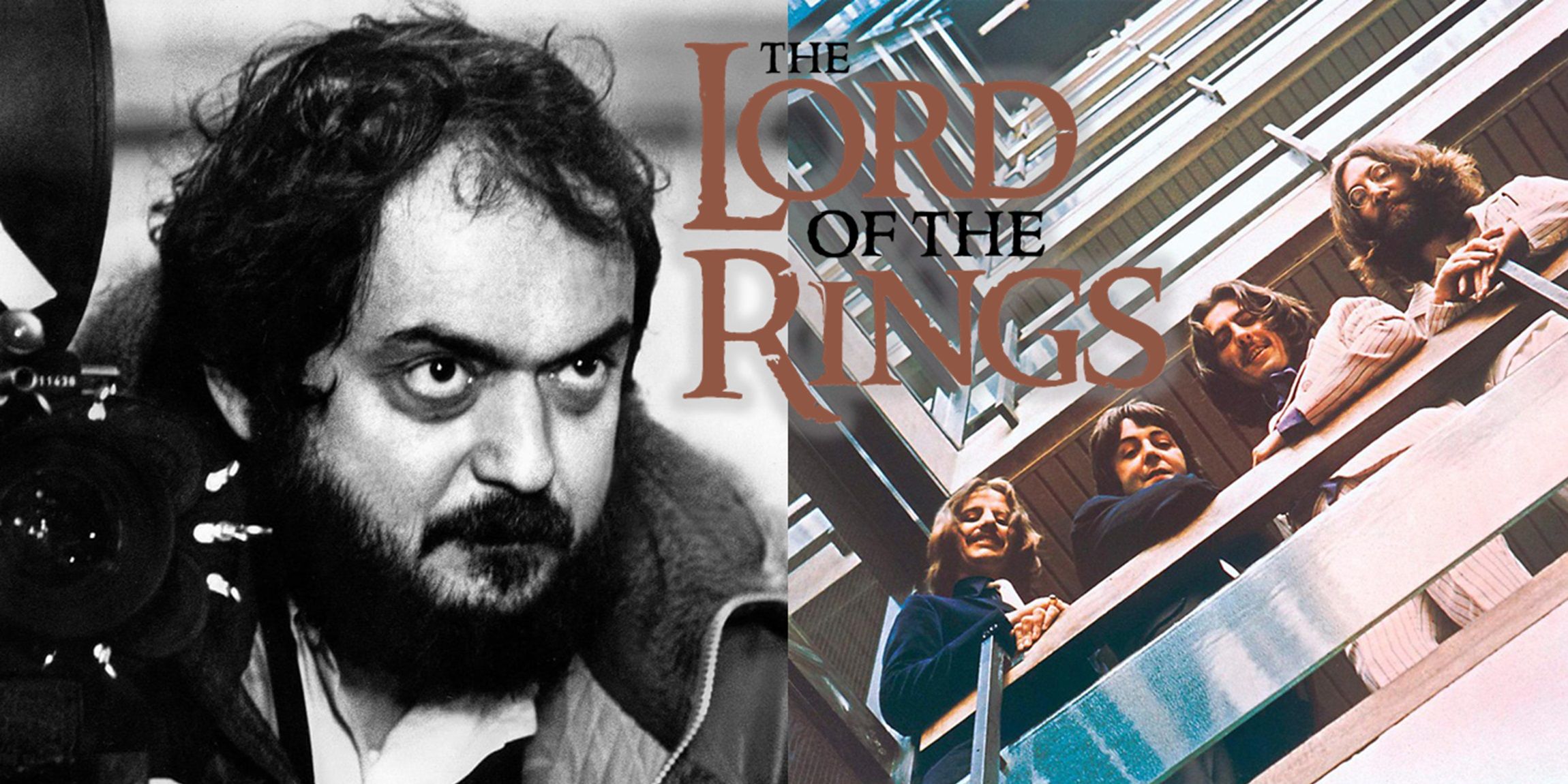

Enter the most unexpected idea of all; a musical version of The Lord of the Rings by Stanley Kubrick, starring The Beatles. The Fab Four were keen to obtain the film rights because they'd grown up loving Tolkien's books and liked the idea of starring in the fantasy adventure. They planned to write the soundtrack, and the project would have starred Paul McCartney as Frodo, Ringo Starr as Sam, George Harrison as Gandalf, and John Lennon as Gollum. Kubrick was The Beatles' first choice as director, and he turned down the idea, believing The Lord of the Rings was too vast and sprawling to successfully adapt. Tolkien himself rejected it when he was approached by his publisher.

In 1969, United Artists - who had acquired the rights to The Lord of the Rings without really knowing what to do with them - asked celebrated director John Boorman to produce The Lord of the Rings. This was envisioned as a single, three-hour-long film with an intermission, and Boorman initially accepted the task out of curiosity more than excitement. "If film-making for me is, as I have often said, exploration," he observed in his autobiography, "setting oneself impossible problems and failing to solve them, then the Rings saga qualifies on all counts." He worked with Rospo Pallenberg on a script that heavily adapted the books and included a sex scene between Frodo and Galadriel. Unfortunately, Boorman's The Lord of the Rings would have been too expensive a project, and in 1970 United Artists suffered a number of financial failures, meaning they didn't have the cash to be spare. "By the time we submitted it to United Artist, the executive who had espoused it had left the company," Boorman recalled. "No one else there had actually read the book. They were baffled by a script that, for most of them, was their first contact with Middle-Earth. I was shattered when they rejected it." The rights were sold on shortly afterward, leading to the first actual animated adaptations.

Peter Jackson first became involved with The Lord of the Rings in the '90s, when he first started work on an adaptation with Miramax. Harvey Weinstein was singularly unimpressed, convinced Jackson was wasting $12 million attempting to make a franchise when he should just be focused on a single two-hour movie. In fact, Weinstein reportedly threatened to have Jackson replaced with Quentin Tarantino if he refused to play ball. "Harvey was like, ‘you’re either doing this or you’re not. You’re out. And I got Quentin ready to direct it’," producer Ken Kamins explained in an interview in Ian Nathan's Anything You Can Imagine: Peter Jackson and the Making of Middle-Earth. Jackson apparently received a slimmed-down script that had cut Helm's Deep, the Balrog, and even Saruman. Weinstein ultimately agreed to let Peter Jackson take his script elsewhere; he found his way to New Line, and the rest is Lord of the Rings history.

from ScreenRant - Feed https://ift.tt/2VcWo0N

via IFTTT

0 comments:

Post a Comment